Military Fires, Defense in Depth, and Future Conflict

Rethinking Operational Depth and Fires Doctrine in the Drone Age

Much of the talk around improving military acquisitions revolves around the need to get drones and technology in the military by 2027. That date shows up repeatedly in the Secretary of Defense’s direction to U.S. Army commanders. The Army talks about that date like it is a finish line. The reason it’s important is there are analysts who think 2027 is the year the PRC has circled on their calendar for reunification with Taiwan. Having technology fielded just in time for crisis is… a way to plan. If those are the dates that are set then the Army needs to start fixing its doctrine, training, and planning now so units will have the ability to use the new equipment when it arrives in 2027.

The Army’s current doctrine for fires and defense in depth hasn’t kept pace with the reality of the modern battlefield. With drones saturating tactical formations and extended-range cannon artillery (ERCA) coming online (maybe, but that is a story for another time), it’s time to ask whether the core assumptions still hold. The short answer? Not really.

Operational Depth No Longer Works

The Army, for all of its complexity, is a simple animal. Their job is to fight America’s wars. But, the simple things are often the hardest so there are pages of theory and doctrine in the U.S. Army. (A caveat, I focus on the Army because, in the end of the day, they are the lion’s share of the fighting force. They have more boats than the navy, more aircraft than the Air Force and their doctrine, because of their size, dictates how the military fights.) One term of art officers will use is “operational depth.” Despite the fancy connotations it means physical space. In describing operations the Army says,

Operations that effectively isolate parts of the system can destroy key components of it in detail. Destroying those components enables rapid tactical maneuver at operational depth and exploits disruptions to the system before the enemy can establish or re-establish the ability to mass effects. Repeatedly exploiting the effects of isolation, destruction, and dislocation ultimately disintegrates the enemy’s ability to resist. Establishing conditions for freedom of action while retaining mobility is critical to creating a relative advantage on the ground for maneuver forces to exploit.

(Emphasis added)

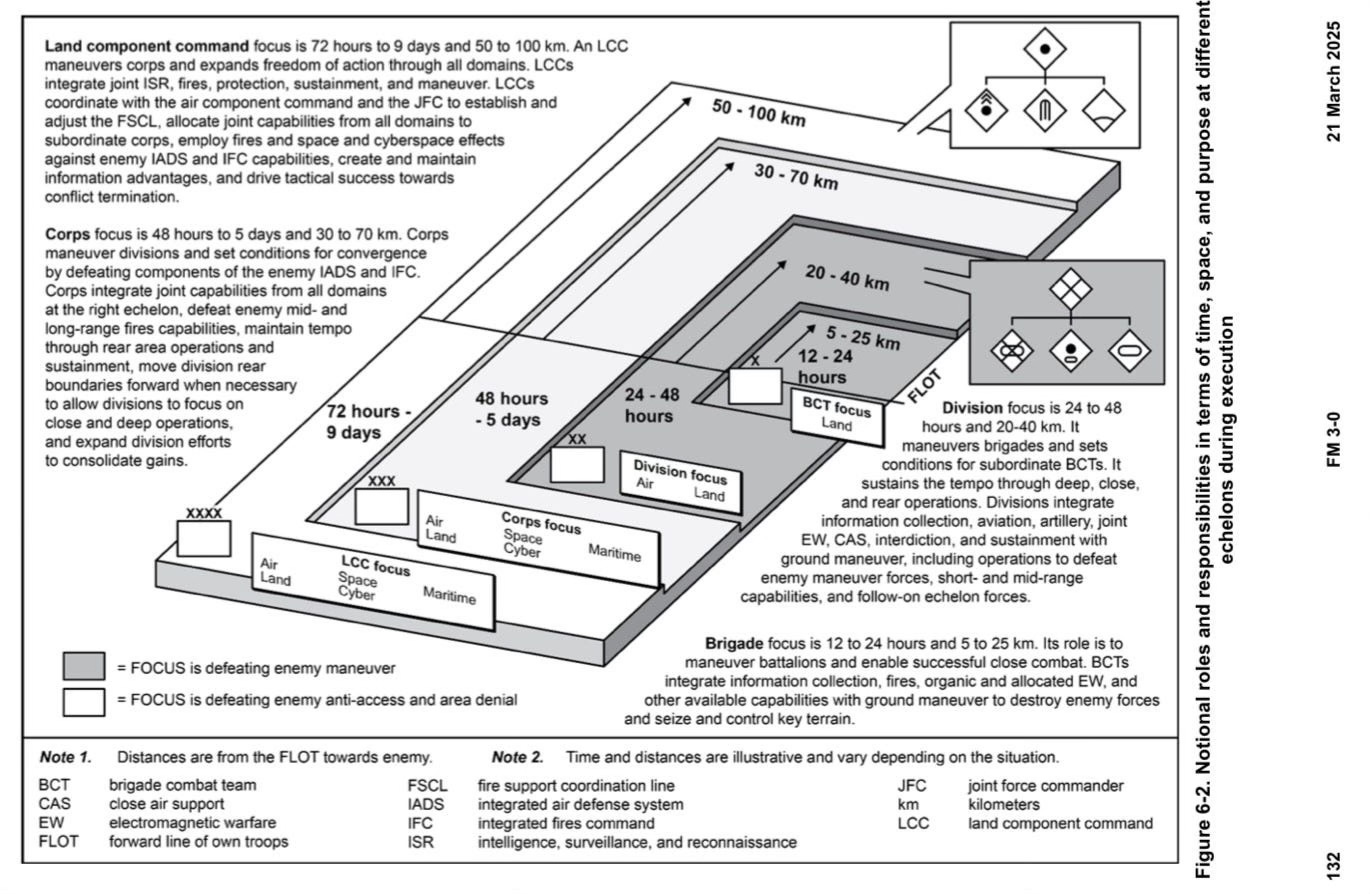

So, operational depth is the distance a force can move, with relative freedom. The Army assumes its operations will provide leaders time, measured in distance, to bring in reinforcements, mass forces, and hold the enemy at arm’s length. That is an industrial aged thought process that no longer fits our world of ubiquitous precision strike, persistent ISR, and long-range fires. In a world where drones and loitering munitions can hit targets hundreds of kilometers behind the front line, there’s no such thing as a “rear area” anymore. Despite this, the Army’s newest operations field manual (FM) 3-0 calls for thinking about time and distance in a way that does not mirror any of the lessons coming out of the Ukraine War. This does not bode well for creating doctrine to adjust to new weapons in 2027.

The Army is still thinking in terms of kilometers and days. They have “notionally” directed a Corps, a formation that commands 20,000 - 45,000 soldiers, to control “Five days or 30 - 70km.” That does not make sense. One-way attack drones can fly hundreds of miles. They can cover 70km in a matter of minutes. This is two dimensional thinking when we should be thinking in domains, cyber, space, electromagnetic spectrum, and the information environment. Depth now has to be created through deception, dispersion, mobility, and resilience.

Today, we’re fielding fires systems that can reach farther than ever before. ERCA will eventually fire out to 70km and beyond. The Precision Strike Missile (PrSM) could push out past 500km. Who is going to control these during a War? The President? We remember the success of Robert McNamara approving target areas in Vietnam. The Army is treating long-range fires as a corps or theater asset. In common terms, that means they are run by three and four star generals. Brigades and divisions are still expected to fight with short-range tools—cannons, mortars, maybe HIMARS if they're lucky. Meanwhile, they’re facing drone-fed kill chains and layered enemy fires that operate at the same ranges as our strategic tools.

This is not a new problem. U.S. artillery has been able to fire rounds 30km for years. Despite the fact that they are commanded by brigade and battalion commanders. That would require a lower commander to speed run an approval up a chain of command to fire outside of his “space”. So we end up in a situation where we’ve given the lower echelons a sniper rifle but told them they need a general’s permission to pull the trigger. That creates real friction. It slows down targeting, bottlenecks fires approval, and leaves commanders without the tools they need to shape the fight in real time.

This delay has already been solved in part. During operations in Afghanistan and Syria, Special Forces teams often controlled artillery and heavy mortars. A 12-man team, augmented by these weapon systems and approved to fire within specific rules of engagement, had the ability to fire well into the “division” area of responsibility depicted on the photo above. Why did they need that ability? Because an armored vehicle, loaded with explosives, traveling 60 mph can cover 30 kilometers in 18 minutes. That is not a long time when you are trying to get a commander on the phone to approve you to shoot into their space. Allowing them to fire as necessary not only protected U.S. soldiers and their partners, but it contributed to defense in depth.

The idea behind defense in depth is to delay and attrit the enemy. Normally, this is done across successive positions. The theory assumes you can see an enemy coming and respond with synchronized fires. It also is layered so even if a single or several positions fall, the defense still holds. This becomes both more critical and more difficult in the age of drones. That’s a tough ask when drones can find you and strike your position before your commander, or you, even knows you’re being targeted. Rather than successive lines of troop positions, defense in depth now requires an additional layer in addition to artillery, rockets, and machine guns. That layering might look like:

First wave - Drone swarms used as mobile sensor barriers.

Second wave (no man’s land) Loitering munitions pre-positioned for reactive strike.

Continuous - EW effects turned on and off to confuse and isolate enemy formations.

Deep operations - Cyber disruptions that delay enemy logistics or ISR.

These aren’t non-traditional fires are still fires. Layering them into a defensive plan and ensuring the lowest levels are empower to use them to their full capability are of paramount importance. And right now, our doctrine just says “integrate it.” What does that mean?

Ok, mister knows-so-much, what do we do about it?

I’m glad you asked.

1. Stop Tying Range to Echelon

The enemy doesn’t care what patch you wear. If a brigade or battalion has sensor data and targeting tools to hit a 300km target, they shouldn’t have to wait for higher HQ approval unless the target has strategic consequences. The ability to give those guidelines are the very reason that commanders from Battalion to God have lawyers. (Forgive the blasphemy its for illustrative purposes.) These lawyers can use the legal authorities to give clear restrictions and constraints to units. Then, once you have empowered lower units, train them. Make them make those decisions, build comfortability with it and make them more aggressively hunt for opportunities to use their assets.

2. Define Fires by Function, Not Formation

We should think about fires in terms of effect, not who owns them:

Close fires: mortars, 155mm, short-range drones

Deep fires: ERCA, loitering munitions, HIMARS

Strategic fires: PrSM, air strikes, space and cyber effects

If you start thinking that way, you stop trying to pull fires into a more concentrated pool and make them more diffuse. By thinking about fires by capability and not by formation we make the organization more efficient. I can hear the protest now. “But, if I send all of the fires down to the lowest level they will waste them and we will not have them when we need them.” To that I say, “The purpose of a thing is what it does, Commander. Rather than gating capabilities behind organizational charts, send them down and exercise some mission command.”

3. Redefine Strategic Depth for the Modern Fight

Depth needs to include deception, mobility, and digital survivability. We need to train our formations to fight without guaranteed access to GPS, comms, or persistent ISR. It also means investing in technology that works in high jamming and without a constant data stream. To do this, units have to train in degraded environments. If only they owned large areas of the country where they could just cut all phone signal and disrupt radio signals at will. This would quickly break the reliance on connectivity and centralized command nodes.

Let me try to address some of the issues I think current officers will have with these suggestions.

“Letting brigades run deep fires is risky. What if they hit the wrong target?”

That’s a fair concern. What if the higher commander fails to make the right call and U.S. solider die? The bigger risk is paralysis. Our adversaries are already doing this. They’re building kill chains that push targeting and fires authority to the edge. If we don’t match that agility, we’ll lose.

“Strategic effects should stay at strategic levels.”

I am not even 100% clear on what a strategic effect is. That is after 20-years in Special Forcers. I was told at times that just being in a place was strategic. If that is true, that means that anything can be strategic and we need to consider what the thing is we are talking about and not just the name of the thing. At a minimum, it is clear the lines blurs between tactical and strategic. A drone strike on a logistics node 200km away can have strategic consequences. Losing a brigade because we tied their hands with bureaucracy would also seem strategic.

“This is too complex to train across the force.”

Well, I guess we should just train for the easy stuff. Low risk operations are sure to be all that is required in the next war. Of course it’s complex. That does not make it any less necessary. The Army is not fighting COIN anymore. They should be preparing for peer conflict under constant surveillance and threat of precision strike. If they don’t learn to operate in that environment now, when the threat is that someone gets a bad report card, they pay for it in blood later.

We are on the edge of a doctrinal tipping point. Drones, ERCA, and AI-enabled targeting aren’t coming, they’re here. Our fires doctrine still acts like it’s 2005 or really 1995 coming off the Gulf War euphoria. If we don’t reframe how we think about depth, authority, and alignment of fires, we’ll find ourselves outmaneuvered before the first shot is fired.