Putting the Cart before the Horse

Trail edge chips are the currency of modern war and the U.S. does not make them

In 1936, the U.S. Navy started work on two of the three aircraft carriers that would go on to win the war in the Pacific. These two Yorktown-class aircraft carriers left the shipyard by 1938. In October 1941, just two months before the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into the war, the Navy completed the third, the USS Hornet. However, their development took longer than the build time suggested. Designers based the Yorktown-class vessels on the older USS Ranger aircraft carrier. The Navy designed and built the Ranger in 1933 after experimentation in how to best build the platforms. The Ranger saw use in North Africa and on protection missions over the Atlantic but its legacy is to be the ancestor of the Yorktown class.

The speed of production and innovation during the pre-war period is remarkable. From the outbreak of the war, the U.S. fielded 22 aircraft carriers. The pace of production only quickened during the war. The Navy ended the war with 33 aircraft carriers in service. This investment in research and development, testing, and production contributed to the U.S.’s ability to fight a two-front war.

The U.S. was in a unique period in its history. It was emerging from an economic depression and asserting its ability to produce on a mass scale. By 1941, the U.S. produced 3.6 million vehicles. In 1939, the U.S. produced fewer than 6,000 aircraft in total. Halfway through 1941, prior to the U.S. entering WWII, the U.S. produced 7,400 aircraft. These were world-leading manufacturing totals and would only increase during the war. Today, the U.S. is not the world’s leading manufacturer. In 2023, Boeing, the primary U.S. plane manufacturer, produced 528 aircraft. This is an area where we struggle. That same year, the U.S. built about 10.6 million vehicles domestically, while China produced 30.1 million.

On pure scale of production this show a weakness in the U.S. abilities but is only part of the issue. Scaling from some to more is easier than scaling from none to one and the U.S. produces almost no trail edge chips.

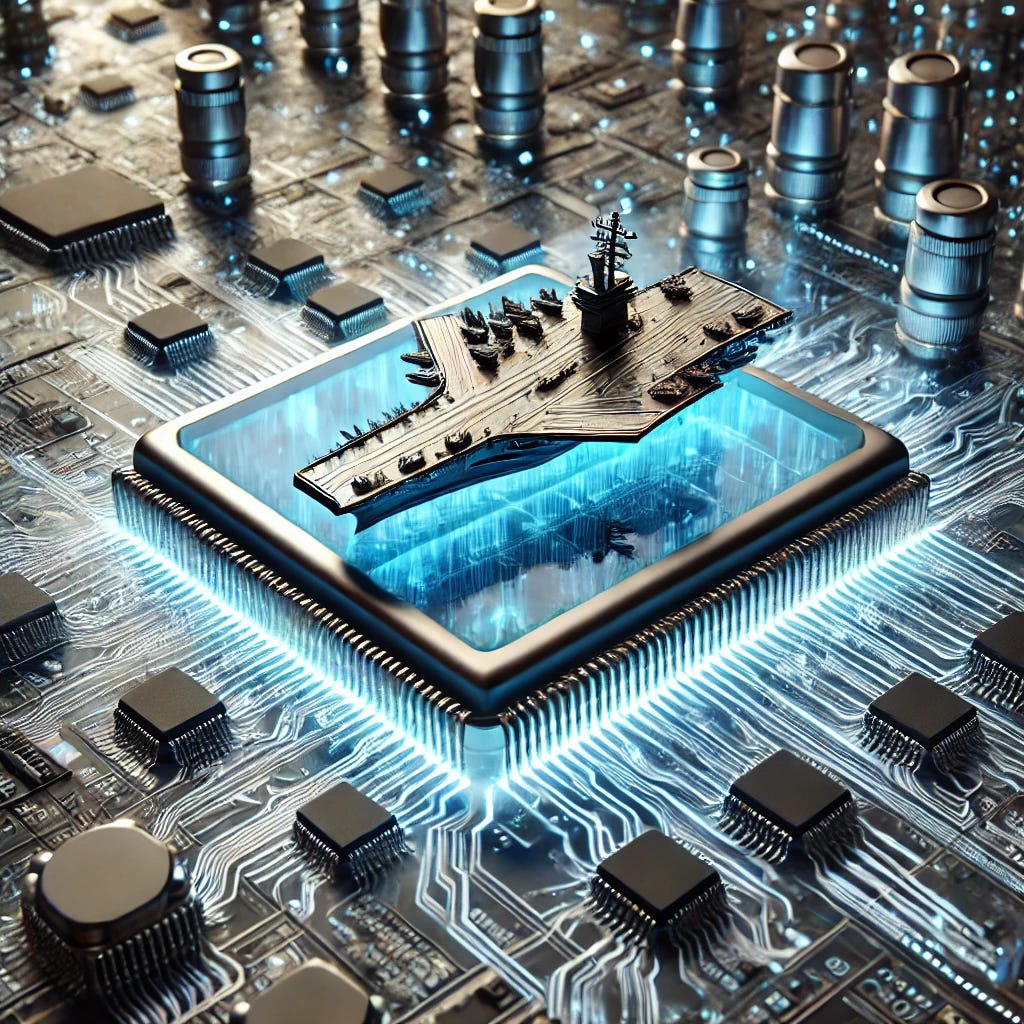

Today’s Aircraft Carrier-Trail Edge Semiconductors

Production capacity was what built the arsenal of democracy. Today, as weapons are more high-tech the U.S. lags behind in production of one of the most critical aspects for future conflict, chip manufacturing. The U.S. is investing in state-of-the-art chip manufacturing. This is an investment for the future economy and technology. Where the U.S. lags behind is in producing trail edge chips. These are the chips that control aspects of vehicle, refrigerators, and, importantly for military uses, tanks and airplanes. As seen by U.S. vehicle manufactures during the COVID supply-chain disruptions, U.S. auto companies rely on TSMC and foreign production of trail-edge chips to complete their inventory.

TSMC has retained production capacity in legacy fabs that far outstrips the rest of the world. China invest heavily in this space and Russian difficulty acquiring chips under U.S. sanctions shows why. China currently produces 28% of world’s legacy chips and aims to increase their market share to 36% by 2030. This means that new entrants in the legacy chip market would face high marginal cost to start new fabs focused on legacy chips and would struggle to find markets for these chips. Without significant government investment it is not an investment a for-profit company could undertake. However, like aircraft carriers and the factories that produce planes and tanks, these need chip fabs need to be in place before war begins.