Thoughts from the Defense Acquisitions Speech

Today’s will be a shorter recap. I worked over the weekend, but I wanted to put fingers to keyboard and discuss Secretary Hegseth’s speech. This is very preliminary. I believe, as I have written before, that the defense industrial base and the military’s acquisition programs need overhauling. Through that lens, I welcome this.

Friday, Secretary Hegseth gave a speech at the Naval Academy. It was 90 minutes focused on the defense industrial base (DIB) and U.S. acquisition policy. Not exactly the kind of speech that will go down in the history books, but acquisition reform is something the Department has needed, and attempted, for a long time. This is a recurring theme from Department Secretaries. Ash Carter started the Defense Innovation Unit (then called DIUx) with a focus on increasing the Pentagon’s touch points with private industry to speed up acquisitions. In 2009, Secretary Gates said, “We need to get past an era where the platforms become so expensive that we can only buy a small number of them.” If these sound familiar, they should. Secretary Hegseth’s recent memos are:

These all amount to the kinds of reforms that past Secretaries have attempted. There are absolutely positives here that are worth pursuing. Key changes like restructuring the incentive system within the Program Executive Offices, reforming Foreign Military Sales, and “putting weapons production on wartime footing” are all positive. However, each faces challenges.

The hardest challenge, without a doubt, is placing U.S. weapons production on wartime footing. There are several reasons for this, and only a very select few of them are bureaucratic in nature. The first problem is, “War with whom?” This may seem self-evident; I assure you, it is not. What does a wartime footing mean? Are we talking about returning to WWII levels of production? During WWII, the U.S. produced “297,000 aircraft, 193,000 artillery pieces, 86,000 tanks and two million army trucks. In four years, American industrial production, already the world’s largest, doubled in size.” If this is what we are talking about, we have to look at the current state of manufacturing in the U.S.

The U.S. is the second-largest manufacturer today, behind China, and that manufacturing base is, by and large, small companies.

The majority of manufacturing firms in the United States are quite small. In 2022, there were 239,265 firms in the manufacturing sector, with all but 4,177 firms considered to be small (i.e., having fewer than 500 employees). In fact, around three-quarters of these firms have fewer than 20 employees, and 93.1% have fewer than 100 employees. With that said, the bulk of employment comes from larger firms, with 59.1% of all employees in the sector working for firms with 500 or more employees.

Ninety-three percent of the manufacturing sector is small companies. This brings us to one of the issues with mobilizing the base. Those small companies are the tier-two suppliers to the weapons manufacturers. They make the connectors, wiring harnesses, and other parts that go into the final products. Telling the primes to invest in themselves does not solve this issue. These small manufacturers live on small margins and are not in a position to take large risks without some guarantee of return. I am not saying that the taxpayer needs to fund everything, but I am saying that placing the economy on a war footing means providing war-footing funding to allow these companies to finance these expansions.

Secondly, there needs to be a real look at how the Pentagon helps small businesses get into the defense ecosystem. Projects like Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC) are the exact type of bureaucratic overreach the Department says it wants to end. When I say this is a burden, to get an external audit for level Two certification the cost for a small business can range from $50,000-$200,000. For a small company this is a large expense. The Department could offer to support small companies through this process, help with onboarding, and even create a collective to help burden-share the requirements. Instead, these types of requirements make small manufacturers reconsider their willingness to participate or work with the military for fear of incurring large upfront costs for a chance to win work.

Reforming Foreign Military Sales is a straightforward proposition, except that it exists outside of the Department’s purview. The FMS process is slow. To quote a defense article from last year: “The U.S., she [Sasha Baker] said, has tinkered with its foreign military system ‘roughly every 18 months for the last 20 years,’ like a car in and out of the shop.” Of course they have. It is a slow process. It requires U.S. government-to-foreign-government contracts, U.S. government-to-U.S. government communication and agreement, and U.S. government-to-industry agreement and communication. Already, these are six major stakeholders who all have to agree and work together. I don’t know if you have ever been part of a group project before, but they normally are not fun and get worse results that all parties think they will at the outset.

One of the key issues is ITAR (International Traffic in Arms Regulations) controls. The Department of State controls ITAR while Commerce controls the Commerce Control List (CCL). This is not just a decision the Pentagon can make and change. Washington Congressman Baumgartner helped pass a law under suspension rules that is supposed to help streamline this process. Eventually, this law, as well as two other laws aimed at the FMS process, may make it through the Senate. This shows that it takes more than action by the Pentagon to make this a reality.

Lastly, there is restructuring the PEOs. There is a great deal to be happy about here. The PEOs and PMs have a great deal of power. They have the power to make or break deals and the power to tip the scales in the direction they want when it comes to acquisitions. Many will hide behind the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR), but the reality is that most of these people are able to wield it as a shield and sword at the time of their choosing. My fear is that reforming their offices to give them more power, but over a more finite time, could create the wrong incentive structure. Instead of them being powerful but having a long view of departmental success and attempting to develop technologies that are going to merge seamlessly with future systems, we could end up with a system focused on creating technological islands. These are systems that would not be forward-integratable because they do not consider a time horizon beyond the next few years.

Defense reform is hard. The reason people lionize Marshall despite his not commanding troops during WWII is he changed the Department of War and the U.S. Army in real and meaningful ways. It is not easy. There is also personal stake in the current system, and when disrupting the current system it is worth remembering that no one is saying “the U.S. makes shitty weapons.” Our high-end capabilities are still bar none. We must balance building more, faster, and cheaper without sacrificing the high end.

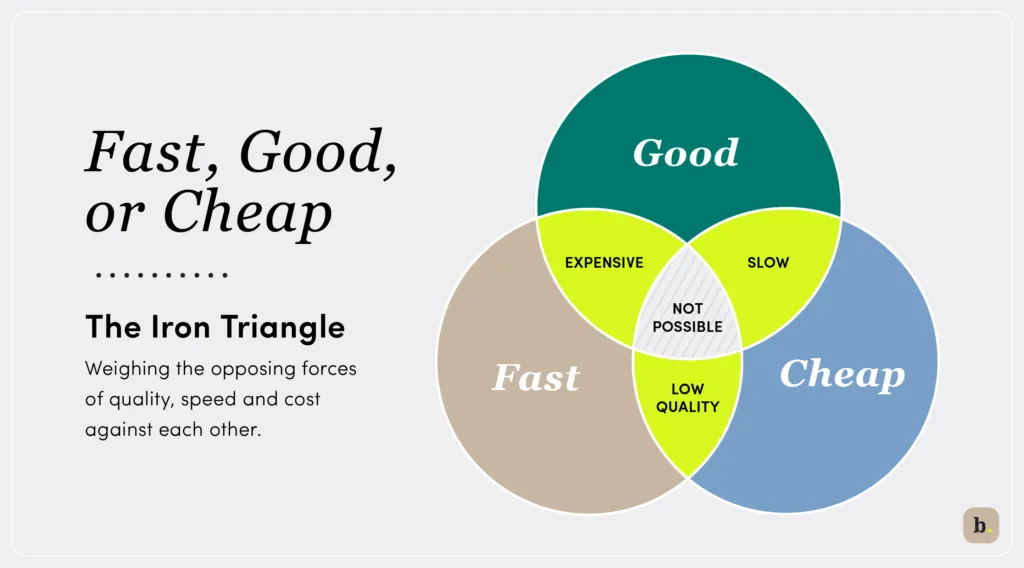

This is hard. The good-fast-cheap triangle is not a law, but it is well-proven. You can have good things cheaply but slow (because no one will make them), cheap things quickly (because you need more of them since they suck), or good things quickly (and they will be so expensive your eyes will water), but you cannot have good, cheap, and fast production. We can, as a nation, do this. We can keep our high end, expand our lower-end production, and develop our industrial base, but we must be clear about the threat, what we are getting on a war footing for, and be ready to spend the money necessary to do it. Like Gates said, we need to get past the point of only buying expensive weapons, but it is nice to have B2s and high-tech weapons we you need them.