Journalism should require nuance

In a quick three minute read over Thanksgiving, The Economist managed to ignite a small firestorm on veteran social media. There was a lot of virtue signaling, everything from “if you can’t stand behind our troops, stand in front of them” to “the recruiting office was open to everyone.” What this article could have been, was a look at how far we have come in the care of our veteran population. Instead, it opened with comments about President-elect Trump and Elon Musk’s “DOGE.” It’s unclear what the author intended. But the phrase at the end jumps out “Reducing payments to former soldiers will never be popular, but it would be wise. America’s veteran obsession has gone too far.” I think we would be better off looking into the numbers.

The absurd use of adverbs

Despite the incendiary language at the conclusion of the article, it’s best to begin at the beginning. The article’s title is incendiary and meant to garner a response from readers. The absurdity is supposed to be that “so many,” roughly a fourth, of veterans now qualify for 100% disability with the average disability compensation increasing from 20% in 2000 to 60% in 2024. If only there was an explanation for what changed from 2000 to 2024 that would account for an increase in medical issues and trauma.

The Global War on Terror (GWOT)

The article makes no mention of increased deployments and the longest duration conflict in American history. In fact, a confluence of events occurred to raises veteran payments. First, after September 11th, 2001, the US began operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. The unofficial numbers are that between 1.9 and 3 million troops served in GWOT. Many served more than one tour.1 The article’s only mention of Iraq and Afghanistan is:

“In 2022 President Joe Biden’s pact Act expanded eligibility further, with illnesses such as asthma and chronic rhinitis gaining approval, as some soldiers had picked up the conditions from “burn pits” in Afghanistan and Iraq.”

Laying aside the writer’s use of language normally reserved for picking something up for dinner to describe developing an illness. The increase in rotations to combat zones did occur as the US expanded the pool of qualifying illnesses. In part, this was a correction of past denials of coverage for illnesses suffered by veterans and to ensure future veterans were protected. The fact that the GWOT was ignored in the article is one of many issues.

Veterans are not working?

One of the most compelling pieces of “research” the article offers is:

“Research by Mr Duggan and co-authors finds that disability compensation has reduced employment, with one in five new recipients leaving the workforce after the change in 2001. As nearly 2m additional working-age men have gone on the rolls since then, this implies 400,000 may have been discouraged from work.”

The economic impact of removing 400,000 people from the workforce would have negative repercussions through the economy. That is a huge number. It is also demonstrably wrong if it is not placed within its proper context.

Mr. Duggan’s work was from 2014. In it the researchers note the inclusion of issues tied to Agent Orange use in Vietnam resulted in an increase in veterans leaving the workforce. That seems like a compelling argument, until you place it within the proper context. The US fought the Vietnam War from 1955-1975, making it the second longest conflict the U.S. has undertaken. This means that an 18-year-old serving in Vietnam in 1955 would have been a 64-year-old in 2001. So, what was the reason these veterans left employment? It is not abundantly clear to me that the “lost productivity” is tied only to an increase in disability payments.

In the same article Mr. Duggan claims “During the 1980s and 1990s, veterans were significantly more likely to work than were nonveterans. Today, the opposite is true." More ammunition for the “reduce payments” group. Again, this was potentially true, with nuance, in 2014, but it demonstrably untrue today. The below chart is from the U.S. Department of Labor and shows that veterans are employed at a higher rate than their non-veteran counterparts.2

The Congressional Budget Office Report

The CBO produced a report on veteran compensation in 2023. This is a much more balance and well-researched report. They identify some key issues that led to increased disability payment:

“Those increases since 2000 can be partly attributed to the long conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, the aging of the veteran population, policy changes that have made it easier to qualify for benefits (including more conditions considered “presumptive,” for which veterans do not need to prove a service connection), and an expansion of VA’s outreach efforts. An additional reason could be a cultural change among veterans with regard to applying for VA benefits, resulting in much higher application rates for VA disability compensation and in more conditions per application than in previous service eras.”

This report placed policy decision within the proper context. Two long duration conflicts coincided with an aging Vietnam veteran population and a greater application rates all contribute to the rise in veteran benefits. I think the most underreported reason for the increase is the greater application rates.

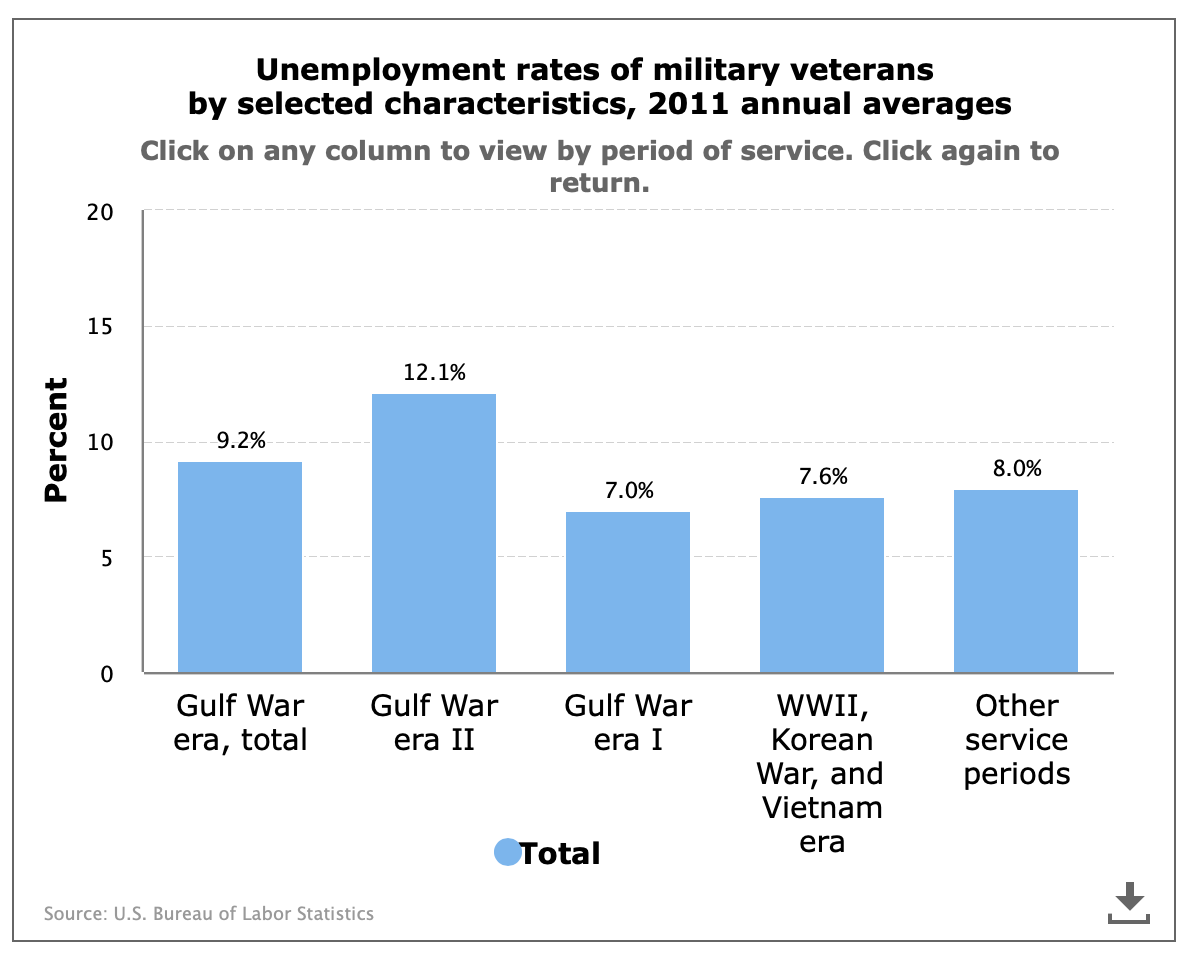

What is the reason for this increase? Well, again, we can turn to nuance and the numbers. In 1991, as the US Military was looking to downsize following the end of the Cold War, congress included a voluntary version of Soldier For Life-Transition Assistance Program (SFL-TAP) in the FY91 NDAA. The goal was to keep soldiers off unemployment and prepare them to transition back to civilian life. However, in 2011, US unemployment was at 8.5%. Veterans were at 8.3%, but for veterans that served after 2001 that number jumped to 12.1%.3 Congress, in response, mandated SFL-TAP. SFL-TAP and its service variants teach Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, and Marines about their benefits. The upshot, now the unemployment rate for “Gulf War II” veterans is 3.2%.4

Conclusion

The Economist article offered one thing, a point of conversation to inject the nuance that is missing from the article and from the discussion of the need to take a chainsaw to the government wholesale. While reform is necessary, it should be guided by comprehensive and nuanced analysis, as oversimplification risks undermining trust in institutions and the welfare of those affected.

Since 2001, between 1.9 and 3 million service members have served in post-9/11 war operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, and over half of them have deployed more than once. Many times that number of Americans have borne the costs of war as spouses, parents, children, and friends cope with their loved ones’ absence, mourn their deaths, or greet the changed person who often returns.

Many Iraq and Afghanistan veterans face a life of disability due to the physical and psychological injuries they sustain in the war zones. Over 1.8 million veterans have some degree of officially recognized disability as a result of the wars — veterans of the current wars account for more than half of the severely disabled veteran population. Many additional veterans live with physical and emotional scars despite lack of disability status or outstanding claims. The costs of caring for post-9/11 war vets will reach between $2.2 and $2.5 trillion by 2050 – most of which has not yet been paid.

https://www.dol.gov/agencies/vets/latest-numbers#:~:text=In%20October%202024%2C%20the%20veteran,from%203.7%25%20the%20prior%20year.

In October 2024, the veteran unemployment rate was 3.0%, up from 2.8% the previous month and up from 2.9% the prior year.

Also in October 2024, the comparable non-veteran unemployment rate was 4.1%, up from 3.9% the previous month and up from 3.7% the prior year.

https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2012/ted_20120323.htm#:~:text=The%20unemployment%20rate%20for%20veterans,all%20veterans%20was%208.3%20percent.

The unemployment rate for veterans who served on active duty in the U.S. Armed Forces at any time since September 2001—a group referred to as Gulf War-era II veterans—was 12.1 percent in 2011. The jobless rate for all veterans was 8.3 percent. Twenty-six percent of Gulf War-era II veterans reported having a service-connected disability in August 2011, compared with about 14 percent of all veterans.

https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t05.htm