Several years ago, I decided to get a masters degree in history. Practical, I know. At the time, I thought I wanted to be history professor. For much of my program, I focused on post-1945 European and U.S. history but my thesis was on the Gulf War. Plenty of military wonks have identified the significance of the Gulf War in U.S. and Chinese military thought. It was a turning point in how the United States projected power and envisioned future conflicts. George H.W. Bush claimed, rightfully, that the U.S. had laid to rest the ghost of Vietnam in the Arabian desert. The U.S.’s use of precision strike, guided munitions, and battlefield awareness enabled by near real-time ISR (intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance), crystallized what came to be known as the American “way of war.” The American way is technologically enabled, globally deployable, and strategically overwhelming. This was the apogee of the American Unipolar Moment and was the final stamp in the Cold War era.

We are approaching, or have already passed into, a new era. One just as dramatic as 1991 and also born of military technological change. This new era is marked by contested communications, AI-driven targeting, hypersonic weapons, and massed drone swarms. None of these change the principles of war, but they do offer us the stark realization that the next generation of conflict will not extend the Gulf War model. In fact, the very technologies that gave the U.S. an edge and formed the core of U.S. doctrine require examination and, I think, a shift in thought.

The Gulf War taught U.S. leaders that speed and precision could deliver near-total victory. The belief that U.S. technology could lift the fog of war became embedded in doctrine and procurement priorities. “Shock and awe” were shorthand for technological overmatch, until the failures in the aftermath of the 2003 invasions ofIraq which saw them turn into pejoratives. Even those failure led only to a doubling down on technology to solve all problems. The U.S. learned to hinge its operational constructs on reliable data streams, centralized command nodes, and exquisite targeting networks. This is a flawed understanding of what actually occurred in the Saudi and Kuwaiti deserts.

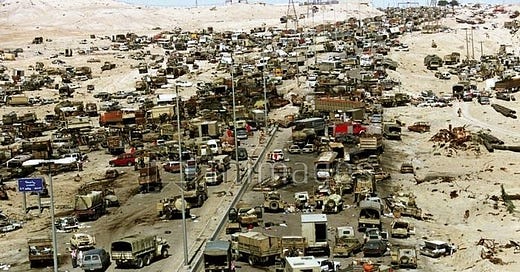

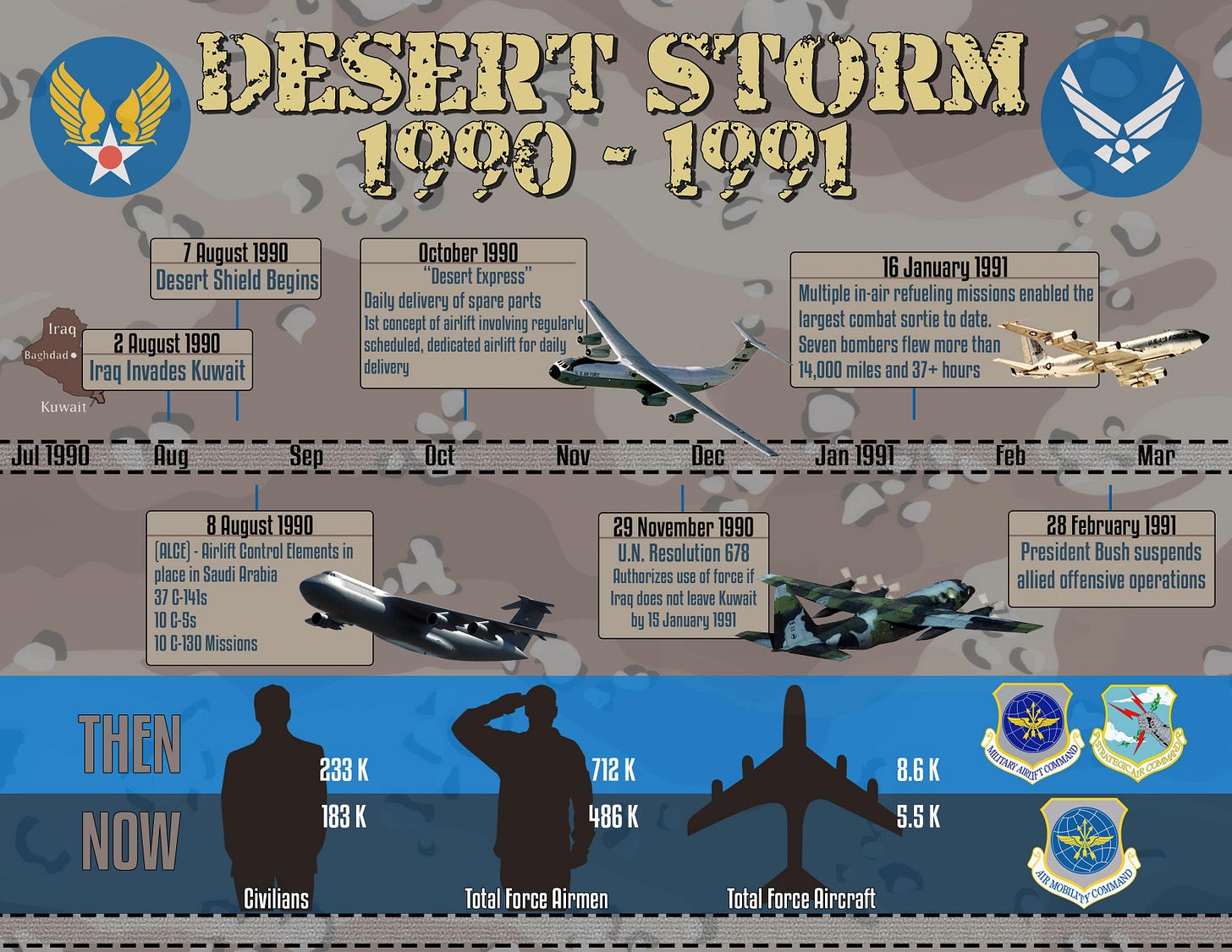

Iraq invaded on 2 August 1990. An often overlooked part of the “100-hour war” is the U.S spent from then until January 1991 building up forces in Saudi Arabia in preparation for offensive operations against Iraq. Time is a safety factor. The more time a commander has the better decisions he will make because he will be able to wargame and stress test his ideas. Iraq gave the U.S. time to buy down risk and ultimately crush the Iraqi Army.

No future enemy worth their salt will allow the US time again. There is a very real possibility that China will target U.S. staging and basing locations among its first targets should they attempt a military occupation of Taiwan. Why would they allow six months, or even six days, of build up on near their borders? Even the threat that the U.S. would intervene in a Taiwan operation is an existential risk to the PRC. A decision to attack the U.S., in particular U.S. forces in Japan, Diego Garcia, or Guam, might seem prudent to the PRC as they would lengthen U.S. response time and they could lessen the chance of intervention in operations against Taiwan. That logic is not drastically different from the Japanese decision to attack Pearl Harbor in 1941 or the German decision to attack Belgium in 1914. Though it may run equal risks or a global war.

In any future war the U.S. will look to allies. Here is another lesson from The Gulf War There is a mistaken belief that the U.S. was able to easily pull together a 42 country coalition to attack Iraq. The false memory of this experience shapes an overconfidence in data supremacy and near-perfect connectivity. Since the Gulf War, U.S. forces expect they will fight under conditions of ISR dominance, secure satellite communications, and full-spectrum information access. These expectations are no longer viable. They also never were.

The cajoling and politics necessary to sign all of the countries up aside, the reality is the coalition barely integrated beyond a superficial level. The Arab contingent of the coalition required Special Forces teams from 5th Special Forces Group to partner with, and sometimes lead, the armies so they could provide accurate locations and keep the higher headquarters informed of the progress of the ground offensive. These partners were often also symbolic. They did not have core tasks. The next war will not be like that. Waiting to attach some Special Forces to an allied unit a day before an attack will do nothing. Instead, those ties need to be developed now, and not with technology, but with constant practice and training.

Ukraine shows us that future battlefields are going to be increasingly degraded or denied environments. Of course they are. The U.S. is not the only nation that took lessons from the Gulf War. The U.S. military needs to be less reliant on centralized control and persistent data links. It must return to the core principles of mission command, build deeper tactical interoperability with allies, and accept the necessity of operating with intermittent or disrupted communications. Those are the weakness inherent in the most technologically advanced force on earth.

China and Russia have developed layered strategies to target satellites, jam communication, spoof locations, and disrupt the data chains that modern U.S. depends on. And that is not allowing for disruptions to the U.S. homeland which is much more susceptible to these attacks because there is no market pressure currently to invest in costly backups as an insurance policy.

Persistent connectivity is a liability, not an asset. The common belief when I was a young soldier was Russians conducted “recon my fire” whenever they detected an enemy signal. That means they would fire artillery at those locations, just in case. We are seeing the same thing in Ukraine. Why would that change in the next war?

In the decades since Desert Storm, the U.S. military has eroded its philosophy of mission command, the command philosophy where units act in a coordinated but decentralized manner around a commander’s intent. Now we see future battlefield will demand units function autonomously. I can hear the protest now. “But, we still have more subordinate initiative than the PLA or Russian Army!” Maybe, but let’s at least consider the lessons they learned from the Gulf War.

One of the most consequential lessons the PLA took fro the Gulf War was the decisive advantage of networked warfare. American success did not hinge on superior weapons but the coordination of those weapons and the “sensor to shooter” loop. Coupled with our world class logistics, that is a tough combination. The PLA recognized that the U.S. military’s abilities did not come from individual platforms. It came from a system-of-systems architecture that linked intelligence, targeting, communications, and maneuver in near real time.

Chinese strategists developed a concept known as “systems destruction warfare.” They would target critical nodes that connect and enable modern military operations. This approach focuses on paralyzing an adversary by disrupting its command and control, ISR networks, logistics chains, and data architecture, rather than trying to match hardware one-for-one and is as revolutionary a change as the U.S.’s technological might in the Gulf War.

Rather than attempt to defeat the U.S. military in a conventional battle of attrition, the PLA aims to fracture the U.S. military’s technologies and their system’s logic. This includes targeting SATCOM and GPS infrastructure to degrade navigation and precision strike capabilities, using cyber weapons to target Joint and coalition command nodes, cyber and space assets to disrupt data flows and ISR integration, and attacking logistics hubs and digital networks to impose paralysis through friction and delay. If the U.S. fights as a system, the Chinese will aim to break system. The result is a logic problem. The U.S. military continues to pursue ever more connected and precise systems as the PLA works to develop an operational philosophy centered on disintegrating those connections. One of those two will work. Future conflict with a great power rival will likely begin with a race for information dominance and system disruption. This is why some see Chinese ownership of the TikTok algorithm and hacks like “Salt Typhoon” as opening salvos aimed at U.S. and allied political power rather than normal great power frictions.

The more advanced our technology becomes, the more essential the human elements of command, leadership, and mutual understanding grow. The U.S. military must rebalance its investment in connectivity with a culture that tolerates and accepts risks and forces commanders and subordinates into areas of discomfort. The most uncomfortable a commander can be is not knowing where his forces are when asked. The most uncomfortable most subordinates are is when they don’t know exactly what to do next and cannot ask. Make that routine.

The Gulf War proved what American military power could achieve under ideal conditions. They can weld overwhelming force, full-spectrum dominance, and near-perfect communication to destroy a less technologically advanced army. But in today’s contested environment, those advantages are not guaranteed. The winners of future wars will be those who can operate effectively in ambiguity.

It's also very under-appreciated the extent to which President Bush and his senior team had spent basically their entire professional (political or military) careers building the types of networks uniquely valuable for this conflict.

We're in a moment when the American public broadly distrusts experts and seriously discounts experience, often IMO for good reasons. And the value experience isn't necessarily something you can elevate in the abstract today. But the more folks learned about the Gulf War, framed as in this post, it would do well to orient folks towards what real and valuable experience can do for folks in positions of leadership.

> There is a very real possibility that China will target U.S. staging and basing locations among its first targets should they attempt a military occupation of Taiwan. Why would they allow six months, or even six days, of build up on near their borders?

If China successfully invaded and occupied Taiwan in short order, the incentive after the fact would be for the US to not declare war. Should the US not be prepared to immediately support Taiwan or doesn't declare war immediately (which seems likely. Why declare war when that would encourage China to interfere with your preparations?), China might gamble on resolving the conflict before the US can intervene. The US felt confident in its ability to successfully invade Iraq, but I'm not so sure how it would see a retaking of Taiwan.

> China and Russia have developed layered strategies to target satellites, jam communication, spoof locations, and disrupt the data chains that modern U.S. depends on. And that is not allowing for disruptions to the U.S. homeland which is much more susceptible to these attacks because there is no market pressure currently to invest in costly backups as an insurance policy.

What do you think about Starlink? There's nearly 10,000 of these satellites in orbit right now, and the only limiting factor on connectivity and data speed are the number of users, which could quickly be limited to civilians during a conflict where this technology is necessary. They've proven useful in Ukraine, and besides initial Russian attempt to hack ground-based Starlink receivers, they haven't been able to jam them due to the sheer quantity necessary (and any ground based installation capable of jamming Starlink signal over a long area would be a very large, and very "loud" target for attack).

The tech seems to be only improving too. Now you can connect to Starlink with any new smartphone. I wouldn't be surprised if connectivity only get easier and more accessible, with militaries have 24/7 unjammable 4k connection to every solider and piece of equipment. Major weather reduces connectivity, though it doesn't eliminate it.